How not to save a company

Imagine the following. Your company is on the verge of bankruptcy. The only way to get out of this is to get all your employees to put in more efforts and energy. To do so, you threaten to cut off their pays because you are dissatisfied with the progresses that they have so far been making. On top of that, you are constantly telling them how little they have been contributing to the company and even how useless they are. At the same time, you are pinning high hopes that they would get your company to be prosperous again.

Does this make any sense? Of course not. But if this is the case, why is it that many northern European countries view – and treat – their southern neighbours so badly? In fact, these latter countries are often called the “periphery”, suggesting that they are far from being as important as the “core” if not depending on it for their own survival. If this does not sound hegemonic enough, the weakest economies – Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain – have been called “PIIGS”. Now, this is blatant bullying. And this does not stop here. What’s worse is that the Eurozone is no Animal Farm: PIIGS cannot stand. By labelling them as livestock, we are effectively saying that they would never be on their feet again.

Perception is deception

There is a common yet deep-seated flawed perception that many people hold: Germany (as the leader of the core countries) would solve the on-going Eurozone crisis. This is likely to be wishful thinking. As I pointed out in my previous blog, Germany is not as strong as it really looks. Other members in the supposedly economically stronger north do not necessarily fare better. For instance, France, the second largest economy in the EU, is struggling to control public finances and raise competitiveness. The Netherlands is likely to remain in recession because its households are over-laden with debt; a quarter of Dutch homeowners are thought to have “negative equity”, meaning that their houses are worth less than their mortgages.

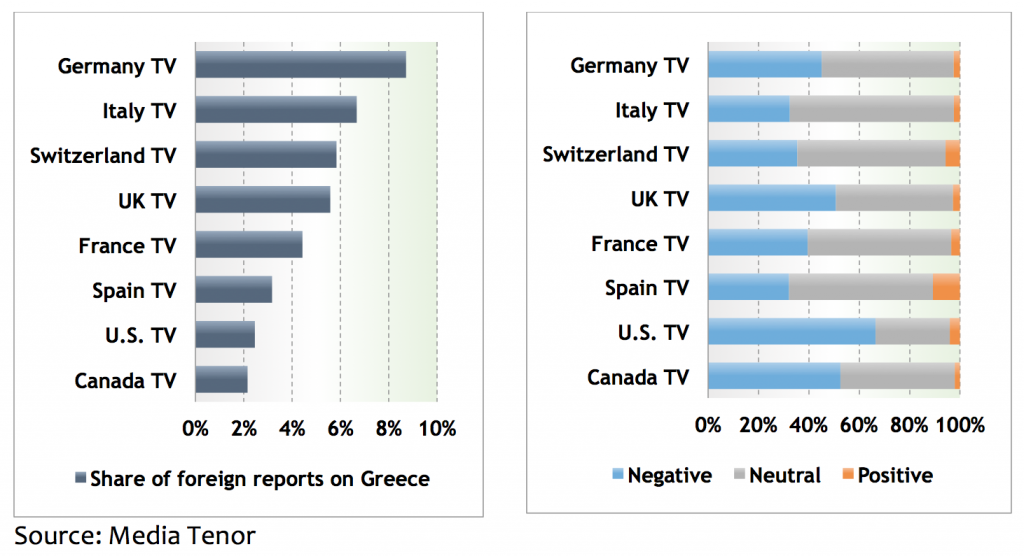

Yet, this popular but misguided perception has led to a more far-reaching problem: While the northern part of the Eurozone continues to be, wrongly, hailed as the saviour of the Eurozone, the southern part continues to be demonised. This is perhaps particularly true for Greece. Even though the country accounts for just 2% of the GDP of the EU, it has received far more than its fair share of negative television coverage from abroad, according to Media Tenor.

Greece: Visibility and tone of coverage on Greece by global media markets, International TV media, 2010-2012

Telling your employees that they are a bunch of under-performers non-stop will never motivate them to rescue your company. Just as if we want the southern countries to be on their feet again, concentrating on the bad news will not help. At the risk of sounding like a self-help guru, I believe that celebrating their successes – as opposed to repeatedly talking about their failures – can boost morale and hence add momentum to reform.

While the news repeatedly reminds us that Greece has not been able to meet the requirements imposed, rarely do we hear what the country has achieved. So, here are some: the country has managed to make the largest fiscal adjustment of any country in history, with more than 12% of GDP in the past three years. The country is ranked number one in terms of responsiveness to Going for Growth report recommendations offered by the OECD. Portugal and Spain also ranked high on the list, with fifth and sixth, respectively. With these, I am not claiming that the southern neighbours are done with all the necessarily reform to revamp their economies – far from it. What I am saying is that we should not only have a lopsided view of the negative aspects of these countries. Indeed, as my thought partner Mark Esposito has pointed out in his blog, the south really has a lot more to offer.

A balanced view will al

low us to be better at thinking about the crisis. After all if we only see our southern neighbours as burden, we are not only missing half the equation to solving the Eurozone crisis; we are also losing most of the intelligence.

πηγή: lse.ac.uk